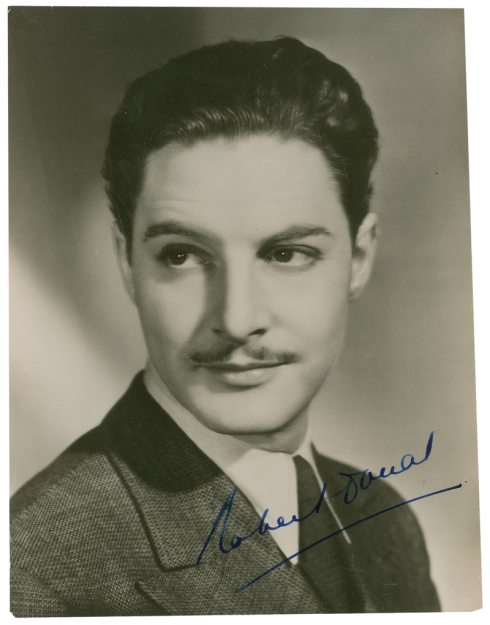

Robert Donat (1905-1958)

In the 1930’s and 40’s, Robert Donat was a household name, Britain’s answer to the big Hollywood stars (his beautiful voice, versatility, charisma, and mastery of stage and screen acting making him a better actor than many of them). Now, a little more than fifty years after he died, he is revered by those who know his work, but amongst the general populace, he is largely forgotten. Nonetheless, he is one of the finest actors Britain has ever produced.

In the 1930’s and 40’s, Robert Donat was a household name, Britain’s answer to the big Hollywood stars (his beautiful voice, versatility, charisma, and mastery of stage and screen acting making him a better actor than many of them). Now, a little more than fifty years after he died, he is revered by those who know his work, but amongst the general populace, he is largely forgotten. Nonetheless, he is one of the finest actors Britain has ever produced.

Robert Donat was born in Withington, Manchester (in the north of England) on 18 March, 1905 and was christened Friedrich Robert. He was the youngest of Emil and Rose Donat’s four sons and was known as ‘Fritz’.

As treatment for a serious stammer, Robert was tutored by elocutionist James Bernard, who taught him to overcome his impediment and lose his Lancashire vowels. Bernard introduced him to many of the skills he would need in what was to become his career and soon spotted the boy’s latent talent for acting. Add to this his enthusiasm for cinema and staging plays with one of his brothers, and perhaps it was not difficult for his parents to see their youngest son was not cut out to be a farmer like his brothers.

When Robert left school, Bernard took him on as his secretary which enabled him to continue his lessons, and he began to perform at dramatic recitals. At the age of sixteen, Robert began his acting career with Henry Baynton’s company at the Prince of Wales Theatre, Birmingham, playing Lucius in Julius Caesar, and in 1924 he joined the famous Shakespearean company of Sir Frank Benson where he stayed for four years (please see Theatre for a full list of all RD’s stage roles). It was with Benson that Robert began to hone his craft and take on major roles, and he supplemented this with seasons in rep.

In 1927, Robert proposed to Ella Annesley Voysey, a young actress he met whilst in rep, and two years later the couple married.

Robert and Ella spent a year together at the Festival Theatre in Cambridge, under Tyrone Guthrie. By this time, Robert was taking leading roles and also tried directing for the first time. His career was progressing and he was keen to make the move to the London stage, so he and Ella took a small flat in Seven Dials and Robert began a rather disspiriting period of trying to win roles. Eventually, a breakthrough came and he made his mark as Gideon Sarn in Precious Bane in 1931, followed by more success at that year’s Malvern Festival.

It was around this time that Robert suffered his first serious asthma attack. There have been many theories about the possible triggers, and Robert himself believed it to be largely psychosematic (asthma was considered a psychological condition by the medical establishment during RD’s lifetime. It was not recognised as an inflammatory disease and treated accordingly until the 1960’s). Throughout his life, he sought a cure, trying many and varied treatments. As time went on, a vicious circle developed, consisting of worry about a possible asthma attack occuring and affecting his ability to work, followed, inevitably, by asthma brought on by the worry, and then more worry about his inability to work and hence more asthma. Despite his many successes, Robert was a sensitive man who sometimes doubted his own abilities and could be easily wounded, though he often realised later if he had overreacted. His papers and letters (collected at The John Rylands University Library) provide a fascinating insight.

The Private Life of Henry VIII

Then, as now, theatre alone provided a precarious living for an actor, so Robert began to pursue film roles to supplement his income. A meeting with Alexander Korda resulted in a three year contract, and Robert began his film career in 1932 with Men of Tomorrow (now sadly lost). His fourth film, The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933) was his first real screen success, and Robert was offered a role in a Hollywood production, The Count of Monte Cristo (1934). It was to be his only visit to Hollywood, and he repeatedly turned down invitations to return. Robert didn’t care for the unsettling feeling that everything, even peoples’ homes, was a film set, and he didn’t wish to be away from his beloved theatre for too long.

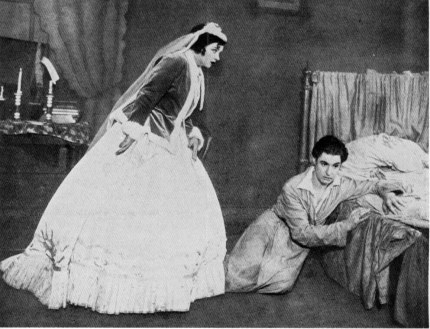

The Sleeping Clergyman

Throughout the 1930’s, Robert worked extensively in theatre, earning excellent reviews in James Bridie’s The Sleeping Clergyman and playing his first ‘old man’ role in 1939, the comedic Old Croaker, in The Good Natured Man. He was almost unrecognisable, disguising his dashing good looks completely and showing his versatility and ability as an accomplished character actor.

The 39 Steps

The Count of Monte Cristo had cemented his film star status and Robert was inundated with offers, many of which he turned down because the quality of the script didn’t meet his exacting standards or he felt he was wrong for the part. It is from this period that many of Robert’s well known films date: The 39 Steps for Alfred Hitchcock; The Ghost Goes West, and Knight Without Armour alongside Marlene Dietrich. During the shooting of Knight Without Armour, Robert’s asthma meant he had to take a break from filming, and Marlene insisted he shouldn’t be replaced, even nursing him herself. Nonetheless, his film career was going from strength to strength and in 1938 he signed a six film contract with MGM British, which would also allow him to continue with his stage work. By now, Robert and Ella had three children: Joanna, John and Brian. Robert saw very little of them during their childhoods, being so often away on stage or filming, but the children got to know their father well as young adults.

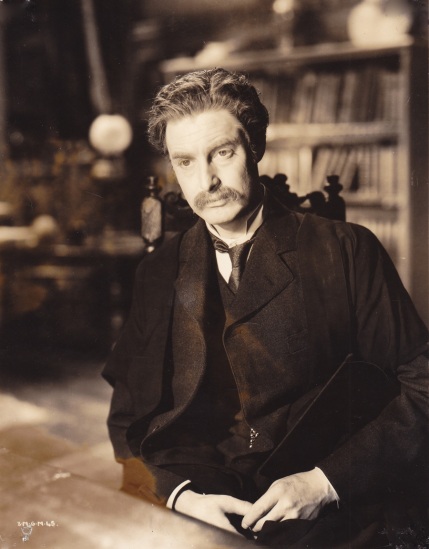

Goodbye, Mr. Chips

Robert’s contract with MGM began well with The Citadel in 1938 for which he won an Oscar nomination. This was followed by Goodbye, Mr Chips, in which Robert played the elderly Mr Chipping, the schoolmaster who looks back on his life at a boy’s boarding school. Robert was required to age from 25 to 83 during the course of the film, and this he tackled brilliantly, winning the Oscar against stiff competition from Clark Gable’s Rhett Butler in Gone With The Wind, which had swept the board in every other category. It’s still a beloved performance. Sadly, Robert’s contract with MGM began to cause him problems during the war years when they attempted to limit his stage work, though they did agree to Robert shooting the propaganda film The Young Mr Pitt for Twentieth Century Fox. By the end of the war, he had made The Adventures of Tartu and Perfect Strangers/Vacation from Marriage and had managed to secure a release from his MGM contract.

In 1943, Robert played another old man on stage, Captain Shotover in GBS’s Heartbreak House. The same year, he realised a cherished ambition to be an actor-manager when he took on the lease of the Westminster Theatre, producing three plays including the Lancashire comedy about the working classes, The Cure for Love, in which he took the lead role. He also produced ‘the first real children’s pantomime’ The Glass Slipper (which he commissioned from Herbert and Eleanor Farjeon) at the St James’ Theatre in 1944 and again in 1945-6.

In the meantime, Ella and the children had moved to America for the duration of the war. Ella had always been very understanding of Robert’s romantic dalliances with his leading ladies, accepting it as an inevitable consequence of being an actor. However, they had grown apart. When Ella and the children returned to England, it was clear the marriage was at an end, and in 1946 she and Robert divorced.

In 1945, whilst producing The Cure for Love, Robert met the young actress who was eventually to become his second wife, Renée Asherson. Robert played Benedick to Renée’s Beatrice in one of his final actor-manager productions, Much Ado About Nothing. Sadly, this play and The Man Behind the Statue pulled in small audiences and Robert suffered substantial losses.

The Winslow Boy

Returning to his film career, Robert took a cameo in Captain Boycott in 1947, and then one of his finest roles, as Sir Robert Morton in The Winslow Boy, in 1948. It was Robert’s wish to return once more to his Lancashire roots, and in 1950, he starred in the film version of The Cure for Love, as well as producing and directing it. It wasn’t a critical success, but Robert had caught the character of the north of England, where the film was enormously popular.

The Magic Box

In 1950, Robert was very honoured to be cast as William Friese-Green, the film pioneer, in the Festival of Britain’s official film, The Magic Box (1951). The film contained cameos from many of the leading actors of the time, with Robert as its star. This was the first time film audiences had seen him on screen in colour.

However, as the 1950’s began, Robert’s health began to decline rapidly and he made a number of visits to specialists overseas. He remained hopeful that the next treatment would bring a cure, but sadly, there was no lasting improvement and treatment proved costly.

Throughout his career, Robert had enjoyed working on radio, including his annual Commonwealth broadcasts and a variety of radio dramas. His poetry broadcasts were especially popular, due to his beautiful voice and deep affinity for poetry. While he was too ill to pursue film or theatre work, and confined to his home, Robert began a very personal project, privately recording his favourite poems. Having the leisure to record and re-record, Robert’s perfectionist approach meant that he worked at his poetry readings until he was completely satisfied with them. They remain a remarkable testament to his skill.

Murder in the Cathedral

In 1953, Robert re-launched his stage career by taking what is widely regarded as his finest role, Becket in T.S. Eliot’s Murder in the Cathedral, directed by Sir Robert Helpmann at the Old Vic. It was a triumph, and Robert’s asthma, though a constant presence, never overwhelmed him (oxygen was kept in the wings, and an understudy was on constant stand by). He received the longest ovation in the Old Vic’s history.

Shortly afterwards, Robert and Renée were married.

Also in 1953, Robert made his screen comeback in a quiet little film, Lease of Life, about a country vicar who finds he has only a short time to live. Robert’s ill health meant his own frailty perfectly suited the character, his breathing difficulties being obvious on camera for the first time, and he gave a very poignant performance.

Perhaps understandably, the serious decline in his physical health meant Robert began to suffer periods of depression, and in 1956 he and Renée separated. Robert’s children tried to raise their father’s spirits, and found that his wonderful sense of humour (Robert was always an incorrigable giggler on set and stage) proved the best tonic for his illness.

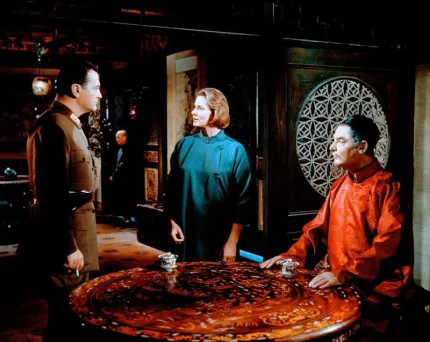

The Inn of the Sixth Happiness

In 1958, Robert took his final film role, as the Chinese Mandarin in The Inn of the Sixth Happiness, the story of missionary Gladys Aylward (played by Ingrid Bergman). He was seriously ill and very frail, but with incredible willpower and utter professionalism, he completed his role and delivered his final line, voice cracking, to a distressed Bergman and a hushed crew: ‘We shall not see each other again, I think. Farewell.’ Soon after, Robert collapsed and was taken to hospital. On 9 June 1958, he died, following a stroke resulting from an undiagnosed brain tumour. He was only 53.

For those of us who are familiar with Robert Donat’s life story it’s all too easy to allow his ill health and tragic early death to cast a pall over our appreciation of his work. There is no doubt that his fragile health prevented him from taking some of the theatrical roles he coveted. But his legacy is not the sad story of a great career blighted by asthma, it is his remarkable work (a fine achievement by any standards), which still brings immense pleasure to anyone who experiences it. He was a truly great actor.

One Response to “Biography”