At long last, Robert Donat’s beloved film, The Cure for Love has emerged from the shadows. For many years, it has not been possible to watch it, aside from a screening of a damaged nitrate print by the BFI in 2005. Happily, it has recently been shown by Talking Pictures TV (and is likely to come round again so do keep an eye on their schedule).

The Cure for Love is also available to watch via this link and if you need a physical copy, and with thanks to subscriber frontrowchris, it can be sourced from Vic’s Rare Films.

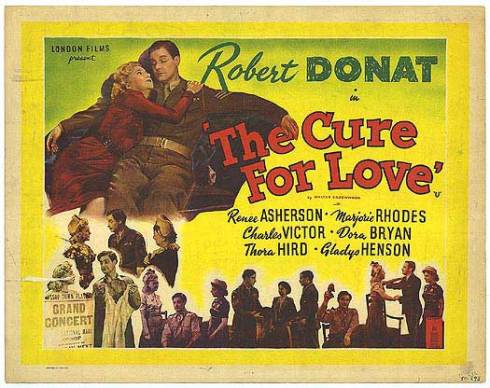

In 1945, Robert Donat appeared as Jack Hardacre in Walter Greenwood‘s play, The Cure for Love, at the Westminster Theatre. Also in the cast was Renee Asherson, who later became RD’s second wife. RD chose to take on the play as part of his tenure as actor-manager at the Westminster. A ‘northern comedy’ set in Lancashire and written by a Mancunian, it greatly appealed to RD who was himself a son of Manchester. Though the run of the play at the Westminster was not financially successful, RD began to think of it as a film venture in which he could achieve an ambition: to be director, producer, writer and star. To bring the film to fruition, RD funded it himself with his fee from The Winslow Boy, and in 1949 it was completed and screened. Though not a huge critical success, it was very popular with filmgoers, and, if comments on this website are indicative, it is very fondly remembered by those who saw it. RD revives his original Withington accent, and if you listen carefully you can hear hints of the stammer his more polished accent cured.

We would love to know what you think of the film: please do comment below.

Please visit https://waltergreenwoodnotjustloveonthedole.com/walter-greenwoods-creative-partnerships/ for more on Walter Greenwood and RD.